The Separate Baptist Revivals in the South,

1750-1790

Garry D. Nation

Whence These Audacious Purposes?

Before the story advances further we must note a facet in the character of the Separate Baptists that recurs at virtually every advance and turning point in their history. Their movement, their decisions, and their success cannot be understood without and understanding of it. Embedded in their approach to religion—and to all of life—was the belief that the Holy Spirit dives direct leadership to the believer.

In the history of Christian enthusiasm few groups have taken firmer hold on the doctrine of the immediate teaching of the Holy Spirit…. After Whitefield had assured them that knowledge of salvation comes through the heart, not the mind, they felt that all revelations of the divine will and purpose should be apprehended in the same way. The new birth meant participation in God's nature and illumination by the indwelling Spirit. The law-within took precedence over every human rule or convention in governing daily life.1

Describing how Stearns personally regarded this issue, Paschal quotes Semple:

Mr. Stearns and most of the Separates had strong faith in the immediate teachings of the Spirit. They believed that to those who sought Him earnestly God often gave evident tokens of his will; that such indications of the divine pleasure partaking of the nature of inspiration, were above, though not contrary to reason, and that following these, still leaning in every step upon the same wisdom and power by which they were firest actuated, they would inevitably be led to the accomplishment of the two great objects of a Christian's life, the glory of God and the salvation of men.2

It was under such motivation and such and understanding of divine guidance while still in Connecticut that Stearns “conceived himself called upon by the Almighty to move far to the westward to execute a great and extensive work.” To ascribe apparently subjective impressions to the Holy Spirit might seem presumptuous, but Paschal observes, “The subsequent events seem completely to have verified Mr. Stearns's impressions concerning a great work of God in the west.”3

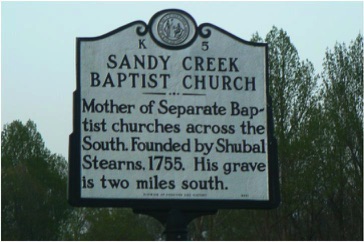

The Sandy Creek Church

It may have appeared that the Separate Baptist pilgrims had wandered into a sparsely populated wilderness. In fact, the time and place of their move could not have been more fortuitous. It was a time of migration as settlers sought out cheap land and lots of liberty. At the same time there was a dearth of spiritual leadership in that area, and people were hungry for it. The spot Stearns chose was at the crossing of wilderness trails in central North Carolina, a place in Guilford County4 called Sandy Creek.

The little band of sixteen wasted no time building a meeting house. On November 22, 1755, they organized as a church, making Stearns their pastor. In spirit of a diversity of language groups in the area, the Separates found enough English folk to keep them busy without crossing cultural lines. Together with co-laborers Joseph Breed and Daniel Marshall, Stearns introduced the astonished settlers to the New Light gospel.

The doctrine of the new birth…they could not comprehend…. Their manner of preaching was, if possible, more novel (to the people) than their doctrines. They had acquired a very warm and pathetic address, accompanied by strong gestures, and a singular tone of voice (from which, perhaps, the singing, or holy tone, of some of their successors, originated). Being deeply affected themselves when preaching, corresponding affections were felt by their pious hearers, which was frequently expressed by tears, trembling, screams, and exclamations of grief and joy.5

In the words of one contemporary observer, “the neighborhood was alarmed and the Spirit of God listed to blow as a mighty rushing wind….”6 It was the New England/Whitefield Awakening all over again, even carrying some of the same phenomena along with it , with people “crying out undr the ministry, falling down as in fits, and awaking in extacies [sic].”7

Shubal Stearns himself, charismatic and influential though he was, left little in the way of a record of his preaching, thinking, or writing. Most of the memory of him is mediated by Morgan Edwards, and English-born Baptist preacher who was called in 1761 to be the pastor of the First Baptist Church of Philadelphia. Around 1770 he was appointed evangelist-at-large by the Philadelphia Baptist Association. A sympathetic observer of the Separate Baptist revivals, he became their chief chronicler. Edwards describes Stearns as being small of stature “but of good nature parts, and of sound judgment”; relatively unschooled but self-taught; and possessing penetrating eyes and a strong, musical voice which he knew how to use to potent effect. “All the Separate ministers copy after him in tones of voice and actions of body; and some few exceed him.” And Edwards saw Stearns as being of “indisputably good” character.8 But surely the most impressive thing about Stearns—and the church—was the “complete dependence on the Holy Spirit…. Scarcely a person attended the early Sandy Creek meetings without being conscious of the spiritual influence which pervaded the place.”9

Stearns also possessed a manifest gift of leadership and administration.10 Though the church's original organization was doubtless very elementary with its pastor and his two assistants, Stearns's leadership approach was to involve every member in the work and worship of the church in primitive New Testament fashion. When they came together for worship someone would bring a psalm, another would bring a testimony, another an exhortation, another a prayer. New converts began witnessing of their faith to others immediately. Women played a large role in public worship as well as private witness, and children also took active part. “All the church felt called to a vast evangelistic ministry.”11

The New Testament was their ideal, and the Sandy Creek Church sought to carry out its ordinances and polities as literally as possible. They settled on nine ordinances or rites: baptism, the Lord's Supper, the love feast, laying on of hands after baptism, foot washing, anointing the sick, the right hand of fellowship, the kiss of charity, and dedication of children. As church officers they recognized ruling elders and elderesses, deacons and deaconesses, and they held weekly communion. As other Separate Baptist churches were formed they apparently looked to this pattern as a model to be considered but not necessarily copied to the letter—something completely in keeping with the Baptist concept of local church autonomy.12 Although traditions varied from church to church, it seems likely that apart from baptism and the Lord's Supper the above practices were observed more or less commonly by the Separate Baptists, perhaps less as required ordinances than as customary expressions of faith and fellowship. (Most Baptists acknowledge and practice only two ordinances, baptism and the Supper, and regard them as memorial observances commanded by the Lord and not as sacraments that in themselves are necessary to faith and salvation.) There is evidence than many of these practices continued to some degree into the early nineteenth century.

Scores of people were experiencing conversions under this preaching, and shortly after a year had passed Stearns and Marshall set out on a mission tour eastward to the coast of North Carolina. They created no small stir, attracting an enthusiastic response from the common folk and a furrowed brow from the political and religious establishment. They may have made another such journey the next year. Stearns finally succeeded in finding an ordained Particular Baptist preacher to help him form a presbytery to ordain Daniel Marshall, and by 1757 Marshall had led the Abbott's Creek group to constitute as a church. Lumpkin, 41-44. Stearns also ordained Philip Mulkey who then organized the Deep River Church by October of that year. Sandy Creek Church now had two daughter churches and over nine hundred communicants between them. At the peak of its ministry the church had 606 or so members, had produced 125 ministers—zealous evangelists one and all—and had given birth to forty-two other Baptist churches.13 Its sudden decline to six members in 1771 (primarily for reasons unrelated to the spiritual condition of the church as will be shown later) in no way diminishes the remarkable influence of its too brief but fruitful life.

Next: The Sandy Creek Association

NOTES

1 Lumpkin, 24.

2 G. W. Paschal, “Shubal Stearns,” The Review and Expositor (January 1939): 45.

3 Ibid., 46.

4 Changed to Randolph County after new lines were drawn in 1779.

5 George W. Purifoy, History of the Sandy Creek Baptist Association (NY: Sheldon and Co., Publishers, 1859): 46f.

6 Morgan Edwards, quoted by Paschal, 47.

7 Edwards, quoted by Lumpkin, 39.

8 Edwards, Materials for a History of Baptists in North Carolina, quoted in G. W. Paschal, History of North Carolina Baptists (Raleigh, NC, 1930), cited in Source p. 17 (1).

9 Lumpkin, 40.

10 Ibid., 38.

11 Ibid.

12 Purefoy, 66-67.

13 Roy J. Fish, “The Effect of Revivals on Baptist Growth in the South, 1740=1845,” in The Lord's Free People in a Free Land, ed. William R. Estep (Ft. Worth, TX: Evans Press), 100.

- II -

“The Same Bringeth Forth Much Fruit”

The Sandy Creek Church Period, 1755-1758