The Separate Baptist Revivals in the South,

1750-1790

Garry D. Nation

A Review of Their Impact

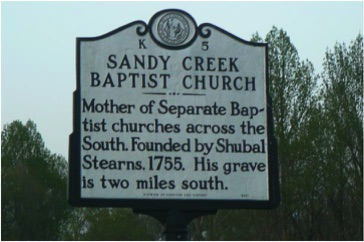

Torbet observes that “on the whole, Baptist growth throughout the colonies prior to the Great Awakening was slow. It was not until that revival of spiritual vigor in the colonies that Baptist began to show a marked increase in numbers and influence.” 1 Before the arrival of the Separates the number of Baptist churches in each of the Southern colonies could be numbered on the hands and the total membership was not significant. Fish gives some idea of the explosiveness of the growth of the Separate Baptists:

In Virginia, by 1793 there were 227 churches, 22,793 members in 14 associations… nearly one third of the whole population of Baptists in America. In North Carolina…by 1784 there were 42 churches and 3,276 members; in 1792 there were 70 churches and 7,503 members. In South Carolina…by 1784 there were 27 churches and 1,620 members. In 1792 there were 70 churches with a membership of 4,167. In Georgia, where the first Baptist church was planted in 1771, Baptists had 50 churches and 3,211 members in 1792. From 1755 to 1792, Baptist churches in the South had grown in number from 28 to 441, an increase of over 1500%. 2

But their influence was more than numerical. Lumpkin calls the Separate Baptist movement in the South “one of the most formative influences ever brought to bear upon American religious life,” carrying as it did the fervor of the New England Great Awakening into the South.3 The Separates came into a spiritual vacuum as it were, speaking the language of the common pioneer. Their faith was deeply evangelical and spoke of the heart's need for regeneration, and they became the earliest popularizers of revivalism. They helped tame the frontier as well, bringing discipline and law to a region where all too often freedom turned into lawlessness. Lumpkin points out further than they made both a material and spiritual contribution to the American struggle for freedom. Their message was far more attractive than what the people were hearing in the “high” churches. The Separates appealed not to the mind nor to the moral will; they called for people to come and let God change their heart. As people received that message they were chaning the whole American approach to religious faith.

More than any other group, the Separate Baptists impressed the revivalistic stamp upon American religious life. It is agreed that “revivalism has proved to be as distinctive of American Protestantism as it has been characteristic.” Other features of American Christianity, including its “strongly biblical, individualistic, parochial, and practical” character, have remained since the Great Awakening. The Baptist contributions fall particularly under the heads of voluntarism, democracy, and denominationalism. They Separate awakening insured the permanence of these elements and of an interpretation of Christianity which was solidly based upon the Bible. 4

Lumpkin also identifies several weaknesses in the movement: too great a dependence on mass evangelism, and excessive emotional appeal; undervaluing ministerial education and training; nonsupport of the ministry; and a too casual approach to theology.5 While he sees all these weaknesses being carried down through later generations, periodically popping up with debilitating effects, there were also wholesome countering influences at work even within the first generation. As the Separate Baptist movement continued and blended with other Baptist movements to become the forbears principally of the Southern Baptists, it matured into a healthy and orthodox denomination with strong missionary and educational institutions.

An Estimation of Their Legacy

It is obvious that the Separate Baptists preached and ministered with boldness and power and unction. It is perhaps easy to overlook the question of where their power came from. It is obvious that the religious experience of the individual was the hallmark of their preaching and their lives. It is easy to overlook that the object of their preaching was to reconcile men to God, that the real question they dealt with was “how shall a sinner be made right with God?”—Luther's question, answered with a very practical and personal application of Luther's doctrine. It is also easy to overlook their strict church discipline and enforcement of personal holiness, alongside a professed belief in the progressive sanctification of the believer.

It is easy to see their great facility with and unabashed use of innovative methods to bring Christ's message to the hearts of men and women, but it is easy to overlook the likelihood that the methods were not so much created for the situation as by the situation. The post-sermon invitation to “come forward” to believe in Christ and be converted, for example, surely did not originate with some evangelist thing up new ways to “catch his fish,” but with a preacher having a compassionate eye seeing a weeping person in his audience and going to him, assuring him he can find relief for his soul in the Lord Jesus.

It is a truism, virtually a cliché, that the Separate Baptists, with George Whitefield as their mentor, preached and adhered to a “modified” or “moderate” Calvinism. But what does that mean? In the case of the Separates it means that, for better or worse, doctrine was not as large a matter for them as was the experience of new life in Christ Jesus, and theology for them only took time away from preaching. The fact remains that when they always eschewed the rationalistic Arminianism of the General Baptists; and when they finally did find time for theology, it was not the evangelical Wesleyan Arminianism of the Methodists they embraced, but the staunch Calvinism of the Regular Baptists of Philadelphia—and their evangelistic spirit did not suffer for it.

They were emotionally demonstrative in their worship and their witness, sometimes excessively so. What must not be overlooked is that in part they were reacting against a style of worship that was rational in the extreme, and that there was more at work in their meetings than emotional flash. Otherwise their success would never have been so enduring.

It is obvious that, being a soul-winning people with an experience-oriented religion, the Separate Baptists were far more concerned with moment-by-moment guidance from the Lord than with principles and ideas that the mind may deduce. What can be missed is the uncanny accuracy of their intuitions, and how often they went to the right place at the right time with the right message.

To me, the most significant element about the Separate Baptists, what made them powerful, what made them grow, what stirred their revival, and what makes them worth emulation is this: their vivid awareness of and dependence upon the Holy Spirit of God. Doctrines, experiences, impressions, methods—all these things are secondary I think to the Spirit of the Lord in understanding the Separate Baptists and what they have to say to modern evangelical Christians. Admittedly, there are no good criteria for evaluating the inner life of anyone. Jesus Christ, however, gave us a useable, practical standard by which we may test a spiritual leader and, by extension, a spiritual movement: “You shall know them by their fruits” (Matthew 7:20). It appears to me that the fruit of the Separate Baptists is good fruit, and fruit that has remained.

NOTES

1 Torbet, 220.

2 Fish, 104-105.

3 Lumpkin, 147.

4 Ibid., 148.

5 Ibid., 148.

- VIII-

"And Ye Shall Bear Witness"

Assessing the Separate Baptist Movement