The Separate Baptist Revivals in the South,

1750-1790

Garry D. Nation

- I -

“I am the vine, ye are the branches”

From the New England Origins of the Separate Baptists until 1755

Whitefield, New Lights, and Separatism

The American preaching tours of George Whitefield in 1740-41 and 1744-45 marked the climax of the great spiritual awakening that swept New England and the Middle Colonies. It was an awakening that emphasized personal conversion, the new birth, the religion of experience. Whitefield's revival movement spawned serval enduring and much copied “innovations.” His preaching style was extemporaneous and emotional, and he held a close rapport with his hearers. He preached for conversion, and his preaching tended to arouse a deep sense of sin and an anxiety for salvation. Thus, conversions often were dramatic and demonstrative. Religious enthusiasm and emotional demonstrations that ranged from the fervent (which Whitefield encouraged) to the fanatical (which he did not) also accompanied these revivals. Other innovative features included the recognition of the itinerant evangelist and lay involvement in ministry.1

Moreover, Whitefield was decidedly unsectarian. An Anglican by birth and ordination and a Calvinist by theology, he welcomed all who would come to hear in any place, and he preached to them a straightforward believer's gospel unencumbered with theological discriminations.2 And though he was no disestablishmentarian, neither was he bound to the established institutions. If the churches would let him he would gladly minister in them, but if not then he would gather his crowds in the streets and fields and hold forth, not sparing any warnings toward an unregenerate profession of Christianity and unconverted ministers.3

The emotionalism and its physical demonstrations (weeping, wailing, laughing, dancing, jerking, falling prostrate) “tended to divide Christians into two camps: those who approved and encouraged such occurrences as evidences of this working of the Holy Spirit and those who strongly disapproved them.”4

Moreover, Whitefield's freewheeling style of preaching, controversy of the “use of means” in getting people to the point of conversion, and his tendency (and his imitators') to sidestep established institutions further polarized the factions that earlier phases of the movement had already created. “Old Light – New Light” schisms were rife throughout Congregationalist and Presbyterian churches. Since the Old Lights, opponents of the revival, tended to possess the institutions, the New Lights found themselves under increasing pressure either to yield their new evangelicalism or to separate from the established churches. Many took the latter course and established their own churches as Separates.

It was not a long step from Separate Congregationalism (that emphasized personal conversion) to Baptist polity, and many Separates made that step. Lumpkin explains:

Affinity between Baptists and Separates rested upon a rather broad basis of agreement. Both advocated a regenerate church membership…and both hated governmental interference with the churches. Bother were wary of interchurch control and favored democratic ideals. The Separates liked the way the Baptists practiced democracy in their churches…. Both groups had an intense interest in religious liberty and represented the discontented element in society. Their views of the ministry and of ordination were almost identical, and, finally, they bore a similar relationship to the same opponents.5

This does not mean that there was an immediate union between the Separates the Baptists. While many of the Separates saw believer's baptism as the only sure way to ensure a regenerate church membership, many others were reluctant to give up pedobaptism, and there were those who still regarded Baptist baptism as sacrilegious. Ultimately, the lines were drawn so that choices and allegiances had to be defined, and the two Separate camps went their separate ways. Those that did not become Baptist eventually either died out or were reabsorbed back into their former Congregational and Presbyterian churches.6

Even those Separates who were re-forming into Baptist congregations were disinclined to unite with the already established Particular (Regular) Baptists. They declined to adhere to the Philadelphia Confession, The Philadelphia Confession of Faith (1742)7, preferring the Bible alone as a guide to faith. They desired more strictness about requiring clear evidence of conversion before admitting new members. Their preaching was more exhortation than exposition. Their worship was more emotional and their zeal more intense than the Particular Baptists. Their whole emphasis was that of the Whitefield revival, and they were anything but “regular.”8

In this volatile environment two men arose with a fateful calling that would in time change the spiritual destiny of the southern United States.

Daniel Marshall and Shubal Stearns

Daniel Marshall was born in Windsor, Connecticut, in 1706. Reared in a devout home he had a deep conversion experience about age twenty and as a young man was elected a deacon in the Congregational church. As his farm prospered he married and had a son but was widowed soon afterwards.

He may have been leaning toward the Separate position as early as 1744, perhaps even declining to have his son christened—apparently criticized by fellow members for advocating views odious to them.9 Whitefield came through his area in 1744, and Marshall was deeply affected by his ministry. By 1747 he had become a leader of the Separates and perhaps already held Baptist convictions. That year he also married Martha Stearns, whose brother Shubal, born in Boston in 1706, had come from a Congregational background into the New Light under Whitefield's ministry in 1745.

Around 1751 Marshall, age forty-five, felt a burning urgency for souls and sold his comfortable Connecticut farm to become a missionary to the Mohawk Indians in east-central New York. He ministered there for eighteen months until tribal strife effectively put an end to his work. We don't know what factors led to it, but he decided to take his missionary work to the south. He traveled with his family southward until he came to Opekon, Virginia where in 1754 he came to a Particular Baptist Church. There he was baptized and licensed to preach—and preach he did! Some thought the excitement engendered by his preaching was disorderly and called on the Philadelphia Baptist Association to investigate. They sent Benjamin Miller, who went in the true spirit of the biblical Barnabas. Not only was he not scandalized, he was delighted with outbreak of revival and encouraged it, writing admiringly of it to the Baptists back in Philadelphia.10

Meanwhile Stearns was on his way to becoming a radical Separate (i.e., Baptist) while serving as pastor of a New Light Congregational church. In 1751 after a thorough study of Scripture regarding baptism he was baptized and withdrew with several members of his church in Tolland to form a Baptist church. He was ordained as its pastor in May 1751.11

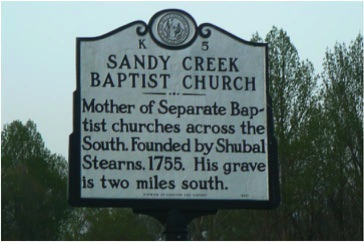

Stearns experienced a strong missionary urgency and set out for Virginia in August 1754 along with five or six couples. They met up with Marshall's family and settled for a time at Cacapon Creek. It was not a fruitful field for evangelism, and Stearns became restless and ready for a change. His Macedonian Call Cf. Acts 16:9. came from North Carolina. Some friends wrote bidding him to come join them. They told him “the people were so eager to hear, that they would come forty miles each way, when they could have opportunity to hear a sermon.”12

In the summer of 1755 Stearns and company set out to answer that call.

NOTES

1 For a full enumeration and discussion of these innovations, see Steve O'Kelly, “The Influence of the Separate Baptists on Revivalistic Evangelism and Worship” (Ph.D. dissertation, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1978), Chapter Two.

2 See William Warren Sweet, The Story of Religion in America, 3rd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1950), 141-2.

3 Lumpkin, 6-7.

4 Robert G. Torbet, A History of the Baptists, 3rd ed. (Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 1963), 222.

5 Lumpkin, 15f.

6 Ibid., 17-18.

7 View here: http://baptiststudiesonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2007/02/philadelphia-confession.pdf

8 Torbet, 223.

9 Lumpkin, 22.

10 Robert B. Semple, A History of the Rise and Progress of Baptists in Virginia, rev. by G. W. Beale (Richmond, VA: 1894), 376, cited in Robert A. Baker,ed., A Baptist Source Book (Nashville, TN: Broadman Press, 1966), 19 (2), hereafter referred to as Source.

11 Lumpkin, 21.

12 Lumpkin, 29.